About a week ago, I got an email from Sefaria announcing that they had acquired rights to share the new JPS Bible translation, at this point just for Neviim but soon for all of Tanach. This new version was titled “The Contemporary Torah: A Gender-Sensitive Adaptation of the JPS Translation.”

The Preface to the work was posted as a Sefaria sheet. It lays out some of its approach and concerns. Also posted was a Dictionary, describing how they treat each word depending on context, for example אדם and איש.

There has been some objection online to this release. Here are two Twitter posts about it.

One:

and another, from the editor at Yated and Mishpacha:

I see that Vos Iz Neias also covers it.

So here are some of my thoughts about it.

Adapting Which Language?

They are adapting the English, not the Hebrew text, and I wouldn’t necessarily say that a particular English translation has inherent sanctity. If JPS wants to mess with an earlier JPS text, so be it.

Semantic Shift

Language changes over time. It is called semantic shift, and is why awful used to mean awe-inspiring, much like awesome. It is why PG Wodehouse wrote about couples making love (meaning wooing) in the park.

Now, “man” used to be somewhat gender neutral, at least in one of its word senses. All men are created equal. To boldly go where no man has gone before. I think ironically because of feminist objections, this gender neutral meaning has faded in recent years. What do you mean “a giant leap for mankind, and not humankind!”

They’ve emended state constitutions to make them gender-neutral, with “he” and “him” replaced with “he or she” and “him or her”. And so folks are primed to think of the regular “he” and “him” as referring only to men.

Given that many people will have that reaction to the text, instead of an education campaign to get people to internalize that these words are actually neutral, why not meet the English speaker where he / she stands, and give them something more intuitive, that captures the actual meaning of the Hebrew text? Why accidentally alienate women who feel that the text isn’t speaking to them? Why give a wrong impression that the verse intended men when it did not?

Which Instances of Man?

The real question is what Hebrew words they are translating as what. It does not seem that they change every instance of “man” to “man or woman”.

Here is an example where they do shift, from Yehoshua 1:18, comparing the 1985 JPS with the Revised JPS. כׇּל־אִ֞ישׁ אֲשֶׁר־יַמְרֶ֣ה אֶת־פִּ֗יךָ וְלֹֽא־יִשְׁמַ֧ע אֶת־דְּבָרֶ֛יךָ לְכֹ֥ל אֲשֶׁר־תְּצַוֶּ֖נּוּ יוּמָ֑ת רַ֖ק חֲזַ֥ק וֶאֱמָֽץ

Should kol ish be rendered as “any man” or should it be “anyone” who flouts your [Yehoshua’s] command… shall be put to death? Did the Israelites think they were only speaking of rebellion males, not females? Presumably not.

Meanwhile, consider the very next pasuk, Yehoshua 2:1:

וַיִּשְׁלַ֣ח יְהוֹשֻֽׁעַ־בִּן־נ֠וּן מִֽן־הַשִּׁטִּ֞ים שְׁנַֽיִם־אֲנָשִׁ֤ים מְרַגְּלִים֙ חֶ֣רֶשׁ לֵאמֹ֔ר לְכ֛וּ רְא֥וּ אֶת־הָאָ֖רֶץ וְאֶת־יְרִיח֑וֹ וַיֵּ֨לְכ֜וּ וַ֠יָּבֹ֠אוּ בֵּית־אִשָּׁ֥ה זוֹנָ֛ה וּשְׁמָ֥הּ רָחָ֖ב וַיִּשְׁכְּבוּ־שָֽׁמָּה׃

Who was sent? How should we translate the anashim meraglim? Surprisingly or maybe not, this is what we get:

It is the revised, “woke” version that has “sent two men from Shittim as spies”, while the old JPS has “secretly sent two spies from Shittim.”

How New Is This Woke Edition?

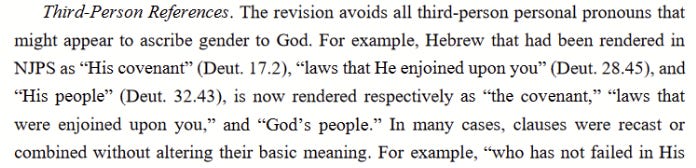

Let us grab an example or three put forth in the VIN article, specifically about revisions in describing Hashem.

We could make the argument that the masculine ending in Hebrew also serves as a a gender-neutral ending, so yes, putting in the noun “God” instead of the pronoun His is not that bad. I would have preferred putting [God] in square brackets in the last example.)

But I am not sure this is entirely new. The comparison is to the NJPS version. Sefaria hasn’t yet updated the Torah translation to the 2023 edition, but I am pretty sure that they’ve had the 2006 edition — meaning one almost 20 years old since February 2022, meaning more than a year ago. That is when Sefaria announced it. The preface and dictionary were composed in 2006.

To look at the three examples — in Devarim 28:45:

and Devarim 17:2:

and Devarim 32:43:

So none of these examples are remotely new in this 2023 “Gender Sensitive” edition. I’m not saying I particularly prefer this 2006 Gender Sensitive edition — I have my dislikes of it for other reasons beyond the scope of this article and beyond gender (e.g. just putting the Hebrew יקוק in the English translation, awkwardness of phrasing, literalness, reordering phrases for flow), and frequently switch to another of the many available translations.

Gnome Ann

There’s the obligatory XKCD that I need to mention in this context.

The title text of the image reads: President Andrew Johnson once said, "If I am to be shot at, I want Gnome Ann to be in the way of the bullet."

What is great about this is not just the awful pun, but the flipping of gender. Instead of the mistaken impression that a specifically male human was intended, we end up with the mistaken impression that a female gnome was intended.

Randall Munroe, the cartoonist behind XKCD, is citing the King James version. Alas, Sefaria hasn’t published the gender-sensitive Mishlei (which is in Ketuvim), but if we look up Proverbs 28:1, we get the following, comparing the JPS 1987 and the Rashi Ketuvim by Rabbi Shraga Silverstein (a real fun translation to try out, with an interpolated, Rashi-based translation / commentary):

נָ֣סוּ וְאֵין־רֹדֵ֣ף רָשָׁ֑ע וְ֝צַדִּיקִ֗ים כִּכְפִ֥יר יִבְטָֽח׃

The wicked flee though no one gives chase,

But the righteous are as confident as a lion.

And Rashi Ketuvim:

נָ֣סוּ וְאֵין־רֹדֵ֣ף רָשָׁ֑ע וְ֝צַדִּיקִ֗ים כִּכְפִ֥יר יִבְטָֽח׃

[When their time comes,] the wicked will flee [and fall] though none pursue, and the righteous [(their heart staunch in the L-rd)] will trust [in Him] as a young lion [(trusts in its strength)].

Though of course most warriors would be assumed to be male, both give the more accurate gender-neutral.

Eleven *Sons* or *Children*?

Another interesting example they mentioned in the Preface was Bereishit 32:23.

Ironically, in some other cases NJPS reads neutrally where a non-inclusive rendering was actually called for. Three examples should suffice. First, NJPS could render yeled contextually as “lad, boy” (e.g., Gen. 4:23, 37:30); yet it unconventionally cast the plural yeladim as “children” in Gen. 32:23 even though in that context the term can refer only to Jacob’s sons (not to his daughter, Dinah).

Here is the new translation, from 2006:

וַיָּ֣קׇם ׀ בַּלַּ֣יְלָה ה֗וּא וַיִּקַּ֞ח אֶת־שְׁתֵּ֤י נָשָׁיו֙ וְאֶת־שְׁתֵּ֣י שִׁפְחֹתָ֔יו וְאֶת־אַחַ֥ד עָשָׂ֖ר יְלָדָ֑יו וַֽיַּעֲבֹ֔ר אֵ֖ת מַעֲבַ֥ר יַבֹּֽק׃

That same night he arose, and taking his two wives, his two maidservants, and his eleven sons, [sons NJPS “children”; Heb. yeladim. Given the specified number, the reference cannot include Jacob’s daughter(s). English idiom warrants the greater gender specificity.] he crossed the ford of the Jabbok.

I don’t know which I would prefer. One could argue that yes, Dinah’s birth was mentioned because of the incident, and the incident with Dinah and Shechem occurred, but generally speaking, the Torah ignores her existence, and just intends children, not including girls in the count. How often are women included in genealogical lists and counts? Of course, the midrash with Dinah hidden in the box, takes sons as intentional. The Torah, meanwhile, could very well have chosen the word banav, which while optionally also meaning children of unspecified gender (because the plural “im” or “av” ending can be masculine or gender neutral, if boys are included), for some reason resonates more as boys. Why opt for the less frequent yeladav?

Different Translations for Different Purposes

Translators are guided by different purposes and methodology as they craft their translation. In this revised translation, the Preface sets out their concerns. And it is a revision of the 1987 edition which had its own goals.

I’m engaged in some digital humanities work on milah mancha, Leitworte, that is repetition in words across the text, perhaps selected deliberately by the Author as a literary device. Some scholars, especially at Yeshiva Har Etzyon, are big on this sort of analysis. And Chazal as well paid attention to parallel matching words — it is called gezeira shava. When Buber and Rosenzweig made their German-language Bible translation, one key goal was to consistently translate the same Hebrew word (or root) to the same German word. So, to take an example, Rabbi Moshe David (Umberto Cassuto, who was more focused on particular numbers of repetitions than they were) noted the sevenfold repetition of ברא in the first two chapters of Bereishit. In the Buber and Rosenzweig translation, they render the words schuf, chuff, and Erschaffensein. For the verse about Nachal Yabbok, here is how they render it:

In jener Nacht machte er sich auf, er nahm seine zwei Weiber, seine zwei Mägde und seine elf Kinder und fuhr über die Furt des Jabbok,

with “Kinder”, meaning children.

In an email from Sefaria yesterday, they note Professor Everett Fox’s translation for Neviim Rishonim are now newly available, and you can select the one that appeals most to you. They describe Fox’s approach like this:

In his biblical translations, Professor Fox pays special attention to the rhythm, alliteration, and word play of the original Hebrew. His decisions around formatting are also informed by the performance of publicly chanting biblical texts.

As I mentioned above, I like the interpolated translation and commentary of The Rashi Chumash, which puts in e.g. about Dinah, while preserving children over sons:

And he arose that night and took his wives and his two handmaids, and his eleven children [(having secreted Dinah in a chest so that Esau not take her)], and he crossed the ford of Yabbok.

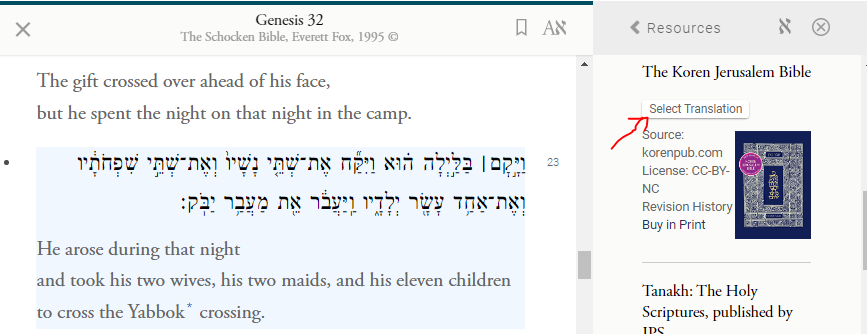

The Everett Fox translation uses line breaks to convey the poetry, thus:

He arose during that night

and took his two wives, his two maids, and his eleven children

to cross the Yabbok crossing.

I am not sure what motivates Sefaria’s selection of default translation. Maybe the one with latest publish date, maybe the gender neutrality. I would personally have gone with Koren. As they note in a recent email, once you shift translations, that selection sticks for you for that particular text. (I’ve had some issue with the stickiness - I think it depends on what you click on to select translations. Merely opening it on the sidebar and closing the original window doesn’t work. You need to explicitly click on the button that says “Switch Translation”)

Here is a short visual of how to switch translations.

Step 1: Click on the text of the verse so that a sidebar opens. Twenty-two translations are available.

Step 2: Click on the word “Translations”. You will see what is labelled “Current Translation”, and little buttons for each to “Select Translation.”

Step 3: Scroll to The Koren Jerusalem Bible and click on Select Translation button. Do NOT simply click on “The Koren Jerusalem Bible” hyperlink or it will show it only in the sidebar, and won’t shift your setting.

Now it switches, in sticky fashion. You can see that because there is now a dark blue badge that states it is the current translation.

Instead of Sefaria trying to bend its readers to a few hyper sensitive feminists, how about such people get over themselves and adapt themselves to the English language as its been written for centuries?

Hi Joshua, I'm Tani Levitt, a reporter with the Forward working on a story about the backlash to Sefaria's Tanach translation update. I'd love to talk to you about your perspective for the story. If this interests you, my email is netanel@forward.com. Thanks!