Have We Truly Left Zevachim? (full article)

Here is my article for the Jewish Link for this past Shabbat. It is an expansion of this earlier Scribal Error post, Stuck in Zevachim, as well as an earlier article, Menachot, and Sugya Dependencies. What is new here is a computation approach, using tools of the digital humanities to quantify the amount of material that is shared between Menachot and Zevachim, vs. what they share with other masechtot. Also, quantifying how much of the shared material, in the form of parallel sugyot, is Menachot-centric vs. Zevachim-centric. There’s also a Jupiter Notebook with all the analyses and charts, and even expansive analysis, so that you can investigate it for yourself by running code cells in Python.

A few weeks ago, those studying Daf Yomi completed the masechet of Menachot and began masechet Zevachim. Even so, it often feels as if we never left. The details and Temple services of flour offerings of Menachot are patterned after animal offerings of Zevachim. Menachot 13b discusses how, for instance, kemitza, scooping flour is parallel to shechita, slaughter and placing the scooped flour in a vessel is parallel to kabbalah. Many sacrificial laws relating to location, time, and intent, play out in similar ways for flour offerings as for animal offerings, and are based on the same underlying principles. Many mishnayot in Menachot parallel those in Zevachim. In Talmudic discussions, it makes sense that both Tannaitic and Amoraic statements from one masechet are quoted in the other masechet, as one has bearing on the other. Indeed, my recent Jewish Link article (“Menachot, and Sugya Dependencies”, January 15, 2026) traced the opening sugya in Menachot as borrowed from the opening sugya in Zevachim, with only a single detail flipped. I demonstrated the Zevachim sugya was primary, and that it in turn drew its components from other related passages in Zevachim. Thus, when learning Menachot, we experience a sense of déjà vu.

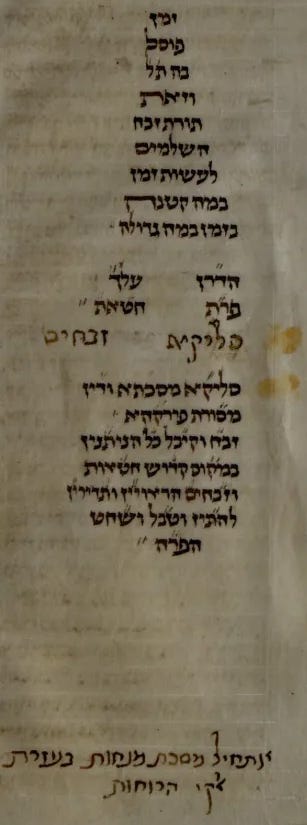

This feeling finds concrete, albeit subtle, expression in the closing page of Zevachim, in the Paris AIU manuscript. The scribe whose handwriting is evident in all of the text of Zevachim and Menachot writes the final words of the chapter, writes hadran alach naming the chapter, leaves a gap, then writes selika masechta to leave the tractate, followed by a masoretic note to recall the chapters of Zevachim. Even so, he did not explicitly say selika Zevachim or note that he is not beginning Menachot. Instead, a different scribe in a different handwriting adds in those messages.

Exploring the Overlap

It might be unfair to say that Menachot is repeating the sugyot of Zevachim, just because we encountered Zevachim first. Perhaps Zevachim borrowed many of its sugyot from Menachot! Also, we might only recognize familiar sugyot from Zevachim because we just learned it. Perhaps there is just as much material from Chullin or Ketubot. I decided to investigate the level of overlap between these masechtot and to classify overlapping sugyot as Zevachim-centric or Menachot-centric. To do this, I employed digital tools and algorithms. Indeed, there is a field called digital humanities, which computationally investigates this sort of question.

One central resource for investigating sugya overlap is Sefaria and their API (Application Programming Interface). Sefaria is a non-profit, open-source digital library. Aside from their website, they provide a way for computer programs to fetch texts and information about those texts. Sefaria divided the Talmud into individual translation units, which are approximately the length of a sentence to a paragraph. Via their website or their API, one can discover links to other textual units, such as commentaries, manuscripts, midrashim, and other Talmudic passages. There is an algorithm created and perhaps run by the folks at Dicta – see the article “Identification of Parallel Passages Across a Large Hebrew/Aramaic Corpus” – they find parallel Talmudic passages based on approximate word overlap.

I used the Sefaria API to fetch all parallel Talmudic passages for each translation unit in Zevachim and Menachot, and thereby determined what percentage of Zevachim links were to Menachot vs. other masechtot, and the same for outgoing Menachot links, to Zevachim vs. elsewhere. I will detail the results below. As we’d expect, since we are discussing parallel passages, there are roughly the same number of Zevachim links in Menachot as there are Menachot links in Zevachim, with slight differences because of peculiarities in the algorithm, in how humans arbitrarily divided translation units, and in relative percentages of material reused.

Of the overlapping passages, are they Zevachim-centric or Menachot-centric? My assumption is that an overlapping passage involving animal offerings originally surfaced in Zevachim, while one involving flour offerings originally surfaced in Menachot. Then, the passages were copied from their original / primary location to the other tractate. While this assumption is plausible, we must note two weaknesses. Some parallel passages may be neutral, in not dealing with either animal nor flour offerings. Further, we might encounter passages in Menachot that lack a parallel, yet seem to have strong Zevachim aspects. Menachot 16b comes to mind, with its פִּיגֵּל בַּיָּרֵךְ שֶׁל יָמִין, even though the application is to flour offerings.

I devised a few ways to classify parallel passages as Zevachim or Menachot-centric, and present the most straightforward approach here. It is based on an English translation (written under Rav Adin Steinsaltz’s direction) of the Talmudic translation units, because English introduces less ambiguity than morphologically complex Hebrew and Aramaic words.

I asked an LLM to devise a list of keywords expected in each tractate’s passages. For Menachot, these included words like meal-offering, mincha, baked, griddle, and pan. For Zevachim-oriented, these included words like peace offering, lamb, turtle-dove, chatat, and meat. The keyword lists are not comprehensive, and I should really refine them, but they can work for a rough estimate. For any parallel passage, we count every instance of each Menachot and Zevachim keyword. If Menachot keywords prevail, it is Menachot-coded; if Zevachim keywords prevail, it is Zevachim-coded; if the keywords are absent or in equal measure, it is neutral.

Some Results

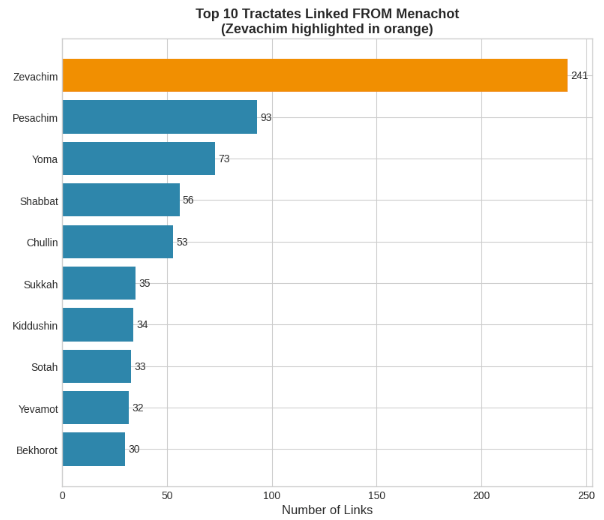

The keyword classification provided the basis for the following quantitative results, which detail the extent and nature of the textual relationship. A fuller analysis is available at my website (girsology.com/notebooks) and contains more sophisticated analysis, such as k-means clustering of parallel passage vectors. Still, I will present a few interesting results here. Looking at Figure 1, the lion’s share of outgoing links from Menachot are to Zevachim (22.8%), and the same is true for Zevachim’s outgoing links to Menachot (23.7%). This makes sense because of shared themes.

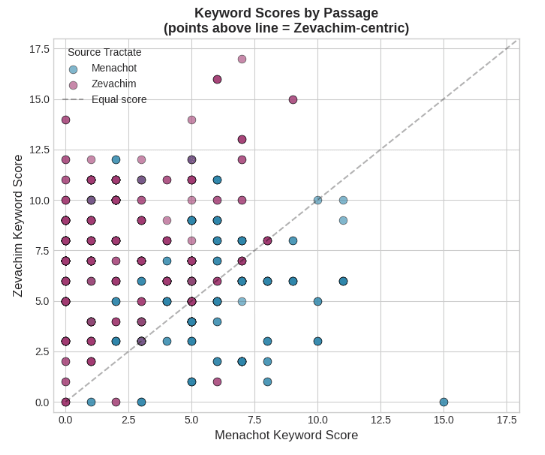

Figure 2 is a scatter plot of Menachot vs. Zevachim keyword scores for 197 parallel passages. Each point represents a passage; blue indicates passages sourced from Menachot, red from Zevachim. The diagonal marks equal scores. In terms of shading, darker blue indicates multiple Menachot passages overlapping at the same score coordinates; darker red indicates multiple Zevachim passages overlapping, and purple tones indicate multiple Menachot and Zevachim passages overlapping. Points above the diagonal have higher Zevachim keyword density.

The concentration of points above the line, including many Menachot-sourced passages, reflects the finding that 72.1% of the shared corpus is Zevachim-centric in vocabulary. There is a meaningful cluster of blue-shaded lines below the diagonal. These are Menachot passages that actually have Menachot-centric vocabulary (flour, meal offerings, omer, etc.). This is expected, and demonstrates that Menachot does have its own distinct topical content, and not all of the shared sugyot appearing in Menachot merely discuss Zevachim topics.

The statistical validation of a Zevachim-centric majority among parallel passages may not be an earth-shattering revelation for seasoned students of the Talmud. Still, the true utility of this digital humanities approach lies in its rigor. By quantifying the textual overlap and vocabulary profile, we elevate our understanding from subjective scholarly impression to an objective, neutrally-derived analysis. This methodological framework provides a compelling, quantifiable basis for the persistent sense of déjà vu linking Menachot and Zevachim, confirming their deep, shared dependency through the precise lens of data science.