Operationalizing Pesak part iv: Initial Assessment of 4o and 4o with search

We’ll get back to theory soon, but at this point, let’s take stock of what we have so far. To quote myself from the Week in Review post:

I begin a series on operationalizing pesak. I try to understand the requirements for a halachically valid pesak halacha, and whether there is such an entity. The eventual aim of this is to consider whether ChatGPT, or any computational mechanism, is able to render pesak.

The first in the series is about gemir and sevir, which is knowledge and analytical ability, though those have different definitions in different contexts. Also, a few other terms and requirements, such as mumcheh, medameh mileta lemileta correctly, and internalized knowledge; and how that might overlap with gemir and sevir. These are in place for both judging monetary cases and for deciding ritual law.

If we wondered whether ChatGPT could render pesak, then two questions we might ask is whether it has these two+ characteristics. (For a later post.)In the beginning of a digression, I consider a halachic question posed by a student to ChatGPT. Assuming a university forbids lighting in the dorm rooms and requires lighting in the dorm building lobby, what is optimal — ignore policy and light in dorm room; light in lobby; or have father light for you in home?

Before any ruling, or critique of ChatGPT’s response (which did indeed have problems), the focus of this post is how a competent posek must know the person and the circumstances; and that ChatGPT skipped all this and didn’t ask several pertinent questions, such as male or female; Ashkenazi or Sefardi; how far away the parents are; and so on. I discuss these and speculate how they might impact a pesak.After listening to the shiur in which Rav Herschel Schachter explicitly addresses this question for the guys on the uptown campus, I give what I think is the correct answer to my student’s question, which differs slightly from my earlier presentation. Moving forward, we can compare AI-generated answers to the query against this halachic analysis I provide.

So here, let us compare against a few answers that ChatGPT provided. Now, ChatGPT has not been trained or fine-tuned specifically on responsa literature, or on interactive chats between a posek and questioner. It is zero-shot, meaning that it has been trained on other material and here we are asking it to render answer a complex halachic query. So perhaps it is not fair. Still, some of the problems found in the analysis of this week answers might well persist in stronger or stronger-seeming answers, just harder to detect. I think it is therefore valid to compare my response with these others. Additionally, such analysis can help to establish expectations for the task, and how it is deeper than we might expect.

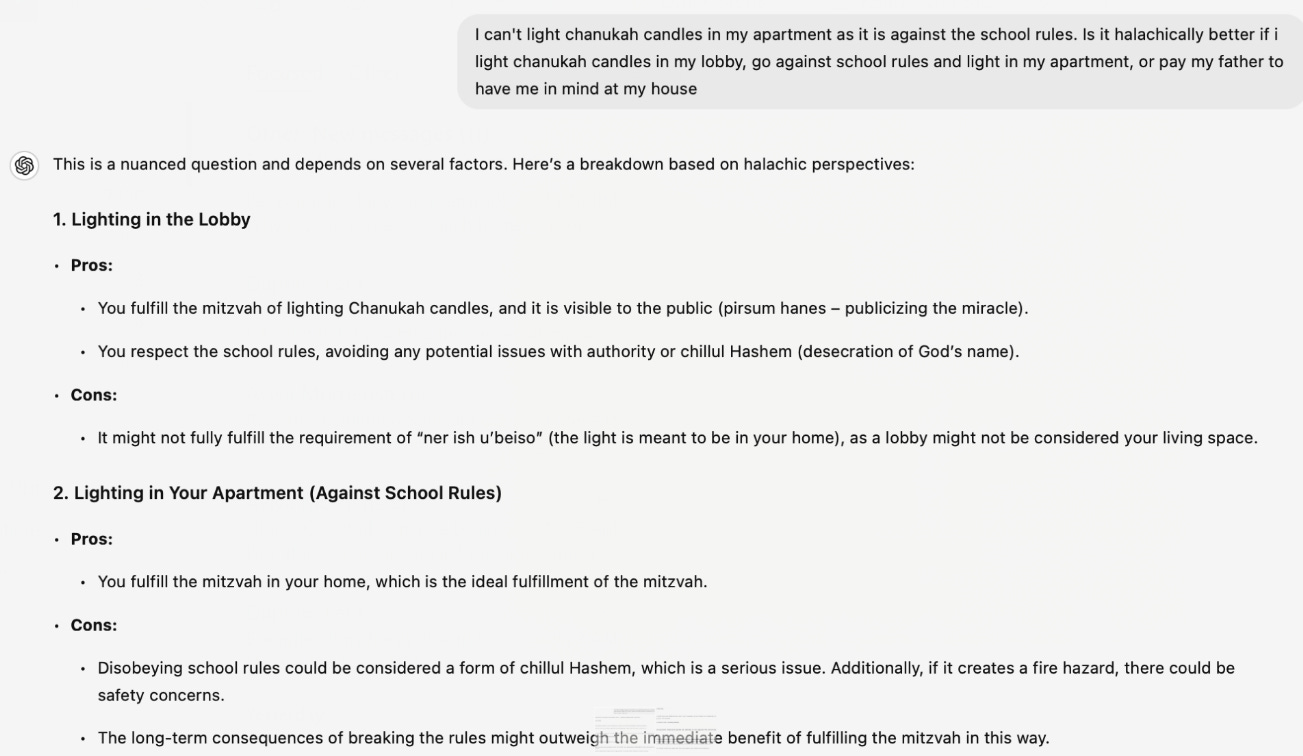

Let us start with the initial conversation about Chanukkah forwarded to me by my student:

The question was not framed well, in terms of paying the father to light on the person’s behalf. That conflated two halachic ideas, of ner ish uveito and what an achsenai must contribute. But someone asking a halachic question isn’t expected to be extremely halachically sophisticated, to understand what issues are pertinent. Similarly, she didn’t specify demographic or situational details that might impact the ultimate halachic ruling.

The answer did identify various halachic considerations which were not supplied by the questioner, and listed the Pros and Cons for each option. The final sentence also recommended consulting a trusted rabbis who understood the specific circumstances.

It did not recommend violating school policies or fire safety, which is ethically aligned. Even though I said the same, and I think Rav Schachter would say the same, because of pikuach nefesh at scale for tightly packed people, I might wonder whether this ethical alignment caused it to land on an answer of the lobby and backing off to relying on one’s father’s lighting, despite violation of school codes empirically being the “optimal” fulfillment of the narrow halachic question of which is most halachically sound to fulfill Chanukkah lighting.

For option 1, lighting in the lobby, the claim that one actually fulfills might be challenged. If the beito requirement is le’ikuva, a necessary component by without which one does not fulfill, then maybe one doesn’t fulfill. Yes, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach held one does fulfill the mitzvah. But lighting in a place which is not your home may well not be a fulfillment of the mitzvah. See for instance Taz 677:2, regarding dinner guests who mistakenly light in their hosts’ homes rather than their own: “this is no different than if they had been standing in the street during candle lighting, where lighting is certainly not applicable.” While noting the “Con” of not fulfilling ner ish uveito, it does not recognize this as an essential component of fulfillment.

Also, it taps the idea of avoiding “chillul Hashem”. You can read the Hebrew Wikipedia article on the halachic concept. But much like marit ayin, there is a popular conception and expansion of the core idea. Here’s an interesting write-up at Nishma.org about whether chillul Hashem refers to perceptions of the out-group of people following Torah law. This may be an inappropriate invocation of the halachic concept1.

For option 2, it does call it the ideal fulfillment of the (core) mitzvah. The cons are chillul Hashem, which again we should think about whether this principle pertains. The other concern about safety rules in not cast in halachic terms, in terms of pikuach nefesh overriding. It seems more like general personal advice, which is a different thing. The same about the “Con” about the long-term consequences. The question was about what is “halachically better”.

For option 3, it echoes the erroneous aspect of “paying” the father to light on her behalf. The pros and cons have aspects of personal advice, regarding avoiding tension and following school rules. It does talk about “many halachic authorities” holding that it is good.

But it doesn’t go into detail about just what the halachic concerns would be; what counts as a bayit; whether you need to be present eventually for someone in the bayit to light on your behalf. I would have ordered the options differently. Overall, it is not so impressive.

And I am not convinced that it is necessarily accurate. I mean, it isn’t based on any behind-the-scenes halachic reasoning system, and it doesn’t “know” anything either. These tokens being generated seem somewhat plausible, but I don’t think that they necessarily would stand up to halachic scrutiny. Again, compare with my own answer in part iii which at least discusses details of why each of the two option would not be considered beito.

I also critiqued it earlier by noting that there were demographic / circumstantial details that could impact the ultimate pesak, such as male/female, Ashkenazi/Sefardi, proximity to the home, and so on.

Now, this was the free version of ChatGPT, which presumably is ChatGPT-4o (but maybe GPT-4). I tried the query with different ChatGPT models, and got some better answers.

For instance, this was the response when I used 4o but with Search enabled. When you do this, it runs a search query on the open web and uses the responses as context when generating the answer. Here is what it generated for the same question:

I can't light chanukah candles in my apartment as it is against the school rules. Is it halachically better if i light chanukah candles in my lobby, go against school rules and light in my apartment, or pay my father to have me in mind at my house?

The answer was:

In situations where lighting Chanukah candles in your apartment is prohibited by school rules, it's important to find a permissible way to fulfill the mitzvah without violating regulations. Here are some considerations:

Lighting in a Common Area: If your dormitory has a common area or lobby where candle lighting is allowed, you can light the menorah there. This approach is often suitable for students in dormitories, as it allows the mitzvah to be fulfilled without breaching any rules. Shulchan Aruch Harav

Relying on Family's Lighting: If lighting candles yourself isn't feasible, you can fulfill your obligation through the lighting performed in your family home. According to halacha, if your family lights the menorah at home with you in mind, you are considered to have fulfilled the mitzvah. This is particularly applicable if you are financially dependent on your family or consider their home as your primary residence. Shulchan Aruch Harav

Avoiding Rule Violations: It's important not to violate school policies by lighting candles in prohibited areas, as adhering to institutional rules is also a halachic obligation. Therefore, lighting in your apartment against school regulations should be avoided.

In summary, if you can light the menorah in a permitted common area, that would be ideal. If not, relying on your family's lighting at home is a valid halachic option. Always ensure to comply with school rules while observing the mitzvah.

Understanding Hanukkah Traditions and Practices (Associated Press: What to know about Hanukkah and how it's celebrated around the world, 8 days ago)

The sidebar also had numerous citations:

It seems to have based itself primarily on the Shulchan Aruch HaRav website, by Rabbi Yaakov Goldstein. So the task is then somewhat like Google search followed by summarization.

As we’ll discuss in a later post be”H, there may be differences between straightforward looking up and application of simple halachah, and reasoning to new situations. This is perhaps somewhere in between. It happens to be a topic that was covered extensively in articles such as that one at Shulchan Aruch HaRav, but does involve complexity and application of halachic principles, instead of reading out from plain straightfoward text in Shulchan Aruch that the blessing on an apple is ha’eitz.

However, in discussing option 1, there is a disconnect between the linked article and the recommendation. The linked article stated “However, if there is worry of fire, the students may light in the dining room2.” The article only mentions a dining room, because a place where you eat is perhaps considered beito. There is a difference between that and a lobby of the building where you sleep. ChatGPT made the these two equivalent.

In certain cases, where you understand the underlying principles, it makes sense to be medameh mileta lemilta. But if you don’t, then you erroneously compare things than should not be compared. To randomly cite something from Kaf HaChaim on Hilchot Shechita:

(ד) שם. ואלו הם שהייה וכו׳ ואין לשאול טעם על הלכות אלו דכולם הלכה למשה מסיני הם. שמ״ח או׳ א׳ והמתחכם לתת טעם על הלכות אלו לאו שפיר עביד דיש דליפוק מניה חורבא כי מדמה מלתא למלתא ועי״ז מכשיל את הרבים.

If you supply your own reasons that aren’t real, then you can extend them to cases where they should not be extended. See also here about being medameh mileta lemileta when one should not.

For the second option listed, this accords with option 3. There is a link to another article on that same website. (Like option 1, it doesn’t mention Rav Schachter’s disagreement if he isn’t actually returning home, but it doesn’t have to.)

In terms of violating school rules, it doesn’t have any link to provide, but stated unsourced that “It's important not to violate school policies by lighting candles in prohibited areas, as adhering to institutional rules is also a halachic obligation. Therefore, lighting in your apartment against school regulations should be avoided.” It would be nice to know where this is stated that such adherence is halachically obligated. It might be, but source it, and not with dina demalchuta dina as another conversation I had put it.

Its ordering of the options is the same. There’s also the air of ethical alignment to the answer; it feels like it couldn’t possibly recommend violating school rules.

This is already getting two long, so I’ll end here. But I have another two ChatGPT models with their answers to analyze, so stay tuned!

Or maybe not. I’ve even invoked the concept of chillul Hashem myself, and cited Rabbis to that effect, about praying on an airplane in a group by the back of the plane and causing hassle to the non-Jewish public, who will think negatively about the Jews. It might be that concept or a related meta-principle. Regardless, it is likely overapplied in many cases by people in a broader sense, so we should think carefully about whether it applies here.

One can argue with that, as it seems Rav Schachter does — that where there’s both eating and sleeping areas, the existence of the sleeping area wins to the extent that the dining area isn’t consider beito.